What or who inspired you to pursue a career in science?

I didn’t set out to pursue a career in science. My first degree is in English and Cultural Studies and I worked in the media and cultural sector for a long while after graduating. I had a great time learning how to share ideas and information in a way that was easy to understand, but I gradually realised that I wanted to find out some things first hand for myself. I started doing some courses with the Open University, stumbled across psychology, and haven’t looked back.

The gap between STEM and the arts and humanities is not as great as it’s sometimes made out to be. I love the creative side of my current job: from coming up with new task designs, to putting together presentations, to developing teaching materials and resources for families, to trying to lay down my ideas clearly in a research paper.

How do you think we can challenge organisational and cultural barriers to gender equality?

A lot of the reward structures and career expectations in STEM are built around the outdated stereotype of the lone, white, male genius who can be massively productive because he does not have any responsibilities outside of the lab. I know too many excellent female scientists who were forced out of the lab because they either didn’t feel they could endure the competitiveness of the publish-or-perish world of academia, or because they couldn’t find or afford the childcare to combine raising a family with working in science. It’s a massive waste of their talent and training, and means we miss out on the perspective that more diverse, collaborative teams can offer. I’ve been lucky enough to have been able to combine a career in science with raising a family because I’ve worked in teams led by researchers who have actively promoted collaborative, supportive and flexible ways of working (Prof Tony Charman and Prof Gaia Scerif I’m looking at you!), and I really hope to do the same – but we need funders and universities to keep improving their incentive systems in order to achieve real change.

Do you think your gender identity brings special skills to your science?

“You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view, until you climb inside of his skin and walk around in it.” (Atticus Finch in To Kill A Mockingbird)

Now Atticus Finch may be fictional, and he may not have ventured into the field of science, but his words encapsulate a problem that has plagued the field of psychology for centuries. In pursuit of understanding human behaviour, scientists have simultaneously ignored and distorted the stark differences between the male and female experiences. While Freud’s ‘hysteria’ was too often used to dismiss female mental health issues, less controversial practitioners systematically excluded women from participating in their studies. As such, we have a wealth of knowledge about the mind, based in huge part on data from western, educated, middle-class, Caucasian men.

Not only is this gap in knowledge striking to me because of my gender identity, but it impacts me day-to-day as a woman with ADHD. Symptoms of the disorder have only recently been shown to change across a woman’s menstrual cycle, meaning their medication may change in effectiveness. This is a phenomenon which has been recognised anecdotally among women with ADHD for years.

My gender identity means that I understand the losses that any demographic group left out of scientific study may suffer. This encourages me to think carefully about representation when carrying out my own research, as well as motivating me to study the issues that gender-bias has ignored. Since we cannot climb inside another’s skin to understand them, the best we can do is to include them. Thus, being a woman in science is less of a skill, and more a super-power.

My daughter is due in 4 weeks and my hope for her is that she has the confidence and support around her to thrive in a male dominated industry like STEM, if that is where her interest lies. Training as a clinical psychologist I never felt in the minority as a woman, but since specialising in research I have become more aware of the sexism that creates barriers for female scientists and, particularly, female scientists who choose to have children.

I have been lucky enough to be mentored by incredible female leaders in science in my career (Professor Anke Ehlers and Dr Jennifer Wild) and I would encourage my daughter to seek out strong female role models who are doing work she would like to emulate.

Being a grief researcher, the fragility and impermanence of life is also something that I am often acutely aware of. My advice to her would be to prioritise balance as a rule for living. STEM careers, while being intellectually and professionally fulfilling, can also be demanding and, at times, precarious. Cultivating balance in life and work will help avoid burnout and maintain enthusiasm for your scientific questions.

Finally, another good piece of advice comes from one of my mum’s favourite sayings “ye dinnae ask, ye dinnae get” which basically means there is no harm in speaking up and advocating for your needs.

What or who inspired you to pursue a career in science?

It was mostly by accident. I chose mostly humanities-based A levels, and my work as a Psychology and Linguistics student straddles the boundary between humanities and science. That's the way I like it: I don't want to limit the scope of my research because I'm assuming what science should be.

I ended up studying science because I'm motivated by scientific methods - psychologists spend a lot of time arguing about what these are, but I consider research scientific if it comes from unbiased curiosity: when you simply want to know the answer, without minding what it will be.

What do you think best supports women to pursue careers in EP and STEM subjects?

Science needs to be more open to people with different educational experiences. Not everyone realises they want to be a scientist at school - I didn't - and that's especially true for women and girls because STEM subjects are so stereotypically male-oriented. It's important women and girls know their scientific ability is not defined by whether they thought maths or chemistry was 'for them' at sixteen.

Why do you think we should encourage women and girls into science? Or why does science need more women and girls?

As objective as we try to be, science will always be affected by scientists' identities. Our life experiences affect what research topics interest us, which groups of people we want to study, and the methods we want to use. Without a diverse group of scientists, including women and girls, science will not reflect our diverse world, and we won't get full answers to our questions.

Why is science a good career path for women and girls?

It's a good career path for anyone who wants answers to the questions they ask about the world. That curiosity is not exclusive to men.

What or who inspired you to pursue a career in science?

I have been mostly inspired by my older brother who is doing well in an academic career as a ‘Natural Scientist.’ I mention this as I regard myself as a ‘Social Scientist’, which does overlap with the ‘Humanities.' I get best of both worlds.

If you had a daughter would you encourage her to follow in your footsteps and why? If your daughter (hypothetical or actual!) followed in your footsteps, what advice would you give her?

I would encourage my daughter to follow her own passions and interests. She can still be inspired by my drive and ambitiousness.

What do you think best supports women to pursue careers in EP and STEM subjects?

Ensuing equal opportunities and having women role models are vital. There also needs to be a change in the dialogue and discourses surrounding women in science. I think there is definitely a shift in the right direction.

How do you think we can challenge organisational and cultural barriers to gender equality?

Leading by example, and challenging the barriers structurally from inside out.

Why do you think we should encourage women and girls into science? Or why does science need more women and girls?

The creativity and different dimensions of/perspectives on intelligence that women and girls can offer in science subjects are immense.

What are the challenges to you as a woman in science? What’s good about being a woman in science?

There are many good points to being a woman in science that can override any challenges faced. For me, it helps to always keep in mind the bigger picture of why science is so diverse, vast and important. This thought is great as the diversity, vastness and importance of science allow the inclusion of everyone who wishes to pursue it. Women can do science!

What or who inspired you to pursue a career in science?

My mum was a developmental psychologist and a scientist. This was particularly impressive given the sexist culture of Iran and being a working mother. Her perseverance and love for her work has inspired me in everything I do. I grew up as her pilot participant in all her new studies, seeing first-hand how an idea develops into a study which later changes policy and impacts people’s lives.

If you had a daughter would you encourage her to follow in your footsteps and why? If your daughter (hypothetical or actual!) followed in your footsteps, what advice would you give her?

I now have a 1.5-year-old daughter, Leyla. I hope she will follow in my (and her grandmother’s- who has since passed) footsteps of enjoying whatever she chooses to do every day. Regardless of her actual choice, I hope to teach her how to navigate and challenge the unwritten rules and biases that unfortunately still exist in our society. She is a daughter of two immigrants, and her race and sex will dictate, in subtle (and sometimes not so subtle) ways how others treat her professionally. Benevolent prejudices carpet every social/professional interaction and navigating these are complicated and draining, something I still encounter regularly.

On the other hand, she is a daughter of two immigrants who had the opportunity to leave unstable countries behind and do what they love every single day. It will be a pleasure and a challenge to learn with her how we can use our privilege to support and promote those less privileged.

What or who inspired you to pursue a career in science?

I remember sitting in Biology class in high school, learning about the fact that biological information is encoded by only four nitrogenous bases in DNA and being completely fascinated by it. Immediately, I turned to my Biology teacher and asked her how our brain encoded information and performed cognitive functions. She couldn’t give me an answer I was satisfied with. Exploring that wondrous mystery is what inspired me to pursue a career in science.

What do you think best supports women to pursue careers in EP and STEM subjects?

What best supports women to pursue careers in science are labs that are inclusive and collaborative, and filled with great colleagues and supervisors exploring interesting questions.

How do you think we can challenge organisational and cultural barriers to gender equality?

I still see women getting comments or questions that men would never receive so we definitely need to be more mindful of the language we use and update our expectations.

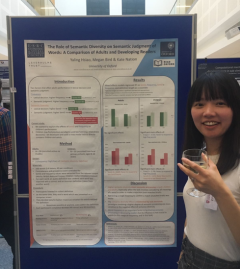

What inspired you to pursue a career in science?

One of my fondest childhood memories is about my father bringing my brother and I to visit the bookstore on the weekend and bought us a book each of our choice. I have always enjoyed reading good stories and from these good stories I learn about how the world works. Often, I enjoy even more “thinking” about how things came to be the way they are. I then try to verify my thinking by looking for answers. It is very satisfying to learn that I was right but equally I feel happy about learning new things if I was wrong. Perhaps this is why I was attracted to experimental research. I find it such a dream-come-true being able to make a living by doing research and learning new things all the time.

What do you think supports women to pursue careers in EP and STEM subjects?

I think it is important to have good mentors that can guide us at different stages of our career. I am very lucky to have great mentors during my Ph.D. and my postdoc. They are not only great academic supervisors and collaborators but also people who can share their life experience as scientists. I also think a friendly working environment makes a real difference. I appreciate the various initiatives that EP offers, e.g. Women’s Tea, Parent Support Group. The university also offers useful resources for staff with caring responsibilities, e.g. generous maternity leave policy, Childcare Services (most with salary sacrifice scheme), the Returning Care Fund. I hope these resources will continue to exist and hopefully be expanded to support more female scientists.